Membership Inferernce Attacks on LLM (Large Language Models)

Introduction

Membership Inference Attacks (MIAs) are designed to determine if a specific data record was used in a model’s training set. Introduced by Shokri et al. in 2017[1], MIAs have since been recognized for their relevance to privacy concerns within machine learning. This introduction will cover the fundamental concept of MIAs and their initial application. Following that, we’ll explore the adaptation of MIAs to large-scale Large Language Models (LLMs) and identify the challenges that diminish MIAs’ effectiveness in this context. To conclude, the discussion will shift to prospective developments and the role MIAs may play in enhancing the privacy of LLMs.

Membership inference attacks

The intuition behind MIAs lies in overfitting of the model to the training data. Overfitting is a common challenge in machine learning, where a model learns too much from its training data, capturing excessive detail that hinders its ability to generalize to unseen data. This occurs when a model, after extensive training, performs exceptionally well on the training data (for instance, achieving 100% accuracy) but poorly on a testing dataset, effectively making random guesses. The root of this issue lies in the model memorizing specific details of the training images—such as the exact pixel positions—rather than learning the broader, general features necessary to distinguish between different individuals’ faces. Although overfitting cannot be completely eliminated due to the model’s inherent limitation of learning solely from its training dataset, various strategies can mitigate its effects.

This concept of overfitting also underpins the differential performance of models on training versus non-training samples, evident through their loss function outputs. For example, a model might show lower loss (e.g., smaller cross-entropy) for training samples than for testing samples. This discrepancy is exploited in membership inference attacks, which aim to determine whether a specific sample was part of the model’s training set based on the model’s response to that sample.

In early implementations of membership inference attacks, the approach involves splitting an original dataset into two parts: one for members (data included in the training set) and one for non-members (data excluded from the training set). The “member” data is used to train a target model, resulting in a model trained specifically on that subset. Subsequently, samples from both the member and non-member datasets are input into the trained model, which outputs a probability vector for each sample if the model is of the classification type. These vectors, along with labels indicating “member” or “non-member” status based on the sample’s origin, are combined with the sample’s true classification label to form a new dataset. This new dataset, referred to as the attack dataset, includes each sample’s probability vector, its true class label, and its membership label. An attack model—a binary classification model—is then trained on this attack dataset to discern whether a given sample was part of the model’s training set.

MIA on LLM

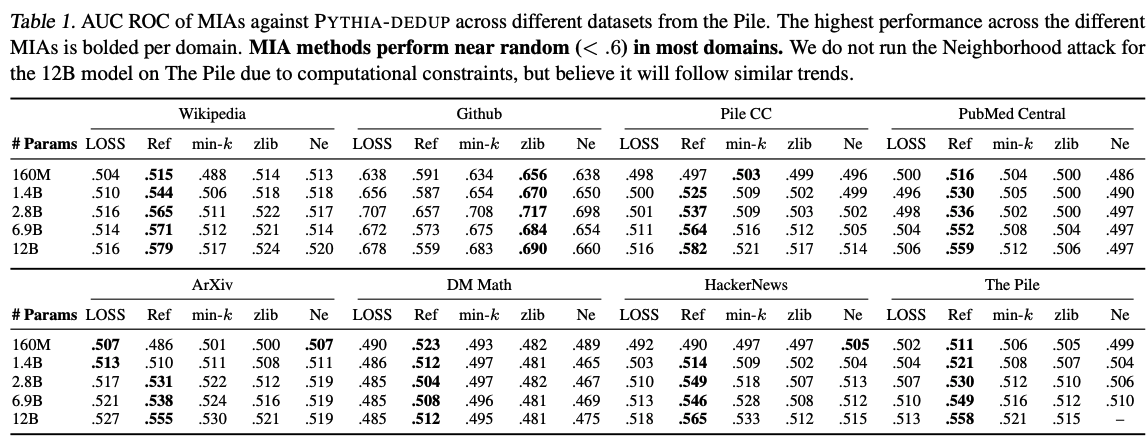

Although MIA has been deeply investigated in small-scale networks, in the era of large languge model (LLM), it is not studied on the LLM enough. Most of the works directly adopt the intuition of MIA-classify the members and non-members based on some indicators (The implementations of the attacks can be found at [6]):

-

LOSS [2]: Considers the model’s computed loss over the target sample. \begin{equation}f(x;M) = L(x;M)\end{equation}

-

Reference-based [3]: Attempts to improve the precision of the LOSS attack and reduce the false negative rate by accounting for the intrinsic complexity of the target point \(x\) by calibrating \(L(x;M)\), with respect to another reference model \((M_{ref})\), which is trained on data from the same distribution as \(D\), but not necessarily the same data. \begin{equation}f(x;M) = L(x;M) - L(x;M_{ref})\end{equation}

-

Zlib Entropy [3]: Calibrates the sample’s loss under the target model using the sample’s zlib compression size. \begin{equation}f(x;M) = \frac{L(x;M)}{zlib(x)}\end{equation}

-

Min-k% Prob [4]: Uses the \(k\%\) of tokens with the lowest likelihoods to compute a score instead of averaging over all token probabilities as in loss. \begin{equation}f(x;M) = \frac{1}{|min-k(x)|} \sum_{x_i \in min-k(x)} -\log(p(x_i | x_1, …, x_{i-1}))\end{equation}

-

Neighborhood Attack [5]: Uses an estimate of the curvature of the loss function at a given sample, computed by perturbing the target sequence to create \(n\) ‘neighboring’ points, and comparing the loss of the target \(x\), with its neighbors \(\tilde{x}\). \begin{equation}f(x;M) = L(x;M) - \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} L(\tilde{x}_i;M)\end{equation}

Why MIA cares

Membership Inference Attacks (MIA) are significant for privacy because they can expose whether an individual’s data was used in training a machine learning model. This might seem technical but has real-world privacy implications, especially in sensitive contexts. For a simple example, consider a machine learning model trained on health records to predict disease outcomes. If an attacker can use MIA to determine that a particular individual’s data was used in the training set, they might indirectly learn something about that individual’s health status, even if the data was supposed to be anonymous.

Imagine a hospital that develops a model to predict diabetes risk based on patient records. If an attacker can apply MIA to this model and discover that John Doe’s data was used in training, they could infer that John might have been at risk of or diagnosed with diabetes, information that’s supposed to be private. This scenario illustrates why MIA is a concern for privacy: it can lead to unintended disclosures of personal information, undermining the anonymity and confidentiality of sensitive data.

Problems in MIA

As research into Membership Inference Attacks (MIA) progresses, several complexities and challenges have emerged. A key question is the interpretation of the probabilities produced by MIA models. For instance, if an MIA model assigns a 60% probability to a sample being a “member” (i.e., part of the training data), the implications for privacy remain unclear. This uncertainty extends to minor modifications of the sample, such as altering a single pixel—does this still warrant a “member” classification, and what does that mean for privacy?

Carlini et al. have highlighted that MIA tends to be more effective at identifying “non-member” records rather than “members.”[7] This observation suggests that the privacy risks associated with membership inference might not be as significant for member samples as previously thought.

Furthermore, the nuances of Large Language Models (LLMs) and their susceptibility to MIAs warrant further exploration. Specific characteristics of LLMs, such as their capacity for data memorization, play a crucial role in how they might compromise the anonymity of training data. However, the full extent of these features’ impact on training data membership remains partially understood.

Given these issues, the future and practical relevance of MIA are subjects of ongoing debate. As we continue to unravel the complexities of MIAs and their effects on privacy, it is crucial to refine our understanding of these attacks and their implications for the security of machine learning models.

Potential of MIA

Recent research highlights the potential of Membership Inference Attacks (MIA) for auditing the privacy of algorithms designed for differential privacy. Differential privacy provides a solid guarantee of privacy, leading to the proposal of differentially private machine learning algorithms, such as DP-SGD and DP-Adam. Users set a theoretical privacy budget, \(\epsilon_{theory}\), and a relaxation parameter, \(\delta\), aiming for the trained model to achieve \((\epsilon_{theory},\delta)\)-differential privacy. However, assessing a model’s actual privacy level has been challenging, as differential privacy offers a worst-case guarantee, suggesting that the practical privacy level might be more stringent (practical \(\epsilon\) is smaller than \(\epsilon_{theory}\)).

Studies now indicate that MIA can estimate the lower bound of the practical \(\epsilon\), denoted as \(\epsilon_{LB}\). This suggests the actual \(\epsilon\) for a model’s privacy lies within the range \([\epsilon_{LB},\epsilon_{theory}]\), providing a clearer picture of its privacy assurances. This insight underscores MIA’s role in evaluating and ensuring the privacy of differentially private machine learning algorithms[8][9][10].

Several differentially private fine-tuning techniques have been developed for Large Language Models (LLMs) to secure their differential privacy [11][12]. Despite these advancements, there remains a lack of research into the auditing of these models’ actual privacy levels. Therefore, a valuable direction for future work could be to employ Membership Inference Attacks (MIAs) to assess and audit the privacy of LLMs that have undergone differential privacy fine-tuning. This approach could provide a clearer understanding of how private the LLMs really are, beyond theoretical guarantees.

References

[1] Shokri, R., Stronati, M., Song, C., & Shmatikov, V. (2017, May). Membership inference attacks against machine learning models. In 2017 IEEE symposium on security and privacy (SP) (pp. 3-18). IEEE.

[2] Yeom, S., Giacomelli, I., Fredrikson, M., & Jha, S. (2018, July). Privacy risk in machine learning: Analyzing the connection to overfitting. In 2018 IEEE 31st computer security foundations symposium (CSF) (pp. 268-282). IEEE.

[3] Carlini, N., Tramer, F., Wallace, E., Jagielski, M., Herbert-Voss, A., Lee, K., … & Raffel, C. (2021). Extracting training data from large language models. In 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21) (pp. 2633-2650).

[4] Shi, W., Ajith, A., Xia, M., Huang, Y., Liu, D., Blevins, T., … & Zettlemoyer, L. (2023). Detecting pretraining data from large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.16789.

[5] Mattern, J., Mireshghallah, F., Jin, Z., Schölkopf, B., Sachan, M., & Berg-Kirkpatrick, T. (2023). Membership inference attacks against language models via neighbourhood comparison. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.18462.

[6] https://github.com/iamgroot42/mimir

[7] N. Carlini, S. Chien, M. Nasr, S. Song, A. Terzis and F. Tramèr, “Membership Inference Attacks From First Principles,” 2022 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2022, pp. 1897-1914, doi: 10.1109/SP46214.2022.9833649.

[8] Tramer, F., Terzis, A., Steinke, T., Song, S., Jagielski, M., & Carlini, N. (2022). Debugging differential privacy: A case study for privacy auditing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.12219.

[9] Nasr, M., Hayes, J., Steinke, T., Balle, B., Tramèr, F., Jagielski, M., … & Terzis, A. (2023). Tight auditing of differentially private machine learning. In 32nd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 23) (pp. 1631-1648).

[10] Steinke, T., Nasr, M., & Jagielski, M. (2024). Privacy auditing with one (1) training run. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36.

[11] Behnia, R., Ebrahimi, M. R., Pacheco, J., & Padmanabhan, B. (2022, November). Ew-tune: A framework for privately fine-tuning large language models with differential privacy. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW) (pp. 560-566). IEEE.

[12] Singh, T., Aditya, H., Madisetti, V. K., & Bahga, A. (2024). Whispered Tuning: Data Privacy Preservation in Fine-Tuning LLMs through Differential Privacy. Journal of Software Engineering and Applications, 17(1), 1-22.